Orthodox Buildings in Latvia

Filaret (Filaretov)

When Filaret (Filaretov, 31 December 1877 to 23 February 1882), formerly the bishop of Uman and rector of the Kiev Ecclesiastical Academy [1], was appointed to the cathedra of Riga and Mitava (Mitau, today Jelgava) at the end of 1877, the Baltic provinces contained 193,988 Orthodox and 149 parishes (123 in Livland, 15 in Kurland and 9 in Estland). In the diocese were 157 churches, including 143 parish churches and 5 home churches. 99 of these were made of stone and 47 of wood: 7 were located in state buildings, 4 in rented abodes, and 23 in “unsuitable accommodations”. According to the same source, 19 churches were in a ruinous condition, 15 were in peasant homes and 7 were in parish schools or the living quarters of clergy. 20 churches lacked iconostases, church utensils, and liturgical books. 10,696 pupils studied in 377 Orthodox schools.

1878-1879 were the last years of the church construction campaign in the Baltic provinces, realised through the Ministry of Internal Affairs [2]. Church construction had been rather delayed under the previous bishop, Serafim (Protopov, 1874-1877). However, Serafim had started work on Riga’s cathedral (3 June 1877) and the construction of the Orthodox seminary (1877). The seminary’s monumental building, constructed in a “semi-church” style which should properly be dubbed “Roman-Byzantine”, was designed by the architect Heinrich Scheel in 1875-1879. The project was the last one that Scheel drew up for the Orthodox Church. The Pokrovskaia church was located in the centre of seminary on the third floor, under a massive helmet-shaped cupola. Orthodox Byzantine architecture was combined with neo-Renaissance allusions: other large educational buildings in Riga were built in this style at the time, including the Polytechnical Institute [3].

Orthodox seminary in Riga

With the appointment of a general governor to Riga, new “rules for the construction of Orthodox churches in Lifland, Estland, and Kurland provinces” were composed and confirmed by the minister of internal affairs on 1 February 1876. From 1876, the head administrator of church buildings in the Baltic provinces was the official and state counsellor Nikolai Artamonovich Kiselevskii.

By 10 February 1878, churches in Mustvee, Maardu, Võnnu, Vanamõisa, Karula-Vissi, Räpina, and Jāņuciems were finished and ready for “transfer to the ecclesiastical domain”. Under Bishop Filaret in 1878-79, a church in the Estonian parish of Jõõpre was built: in the newly opened parish of Tõrva, Estonia, a wooden church was erected.

Jānis Baumanis

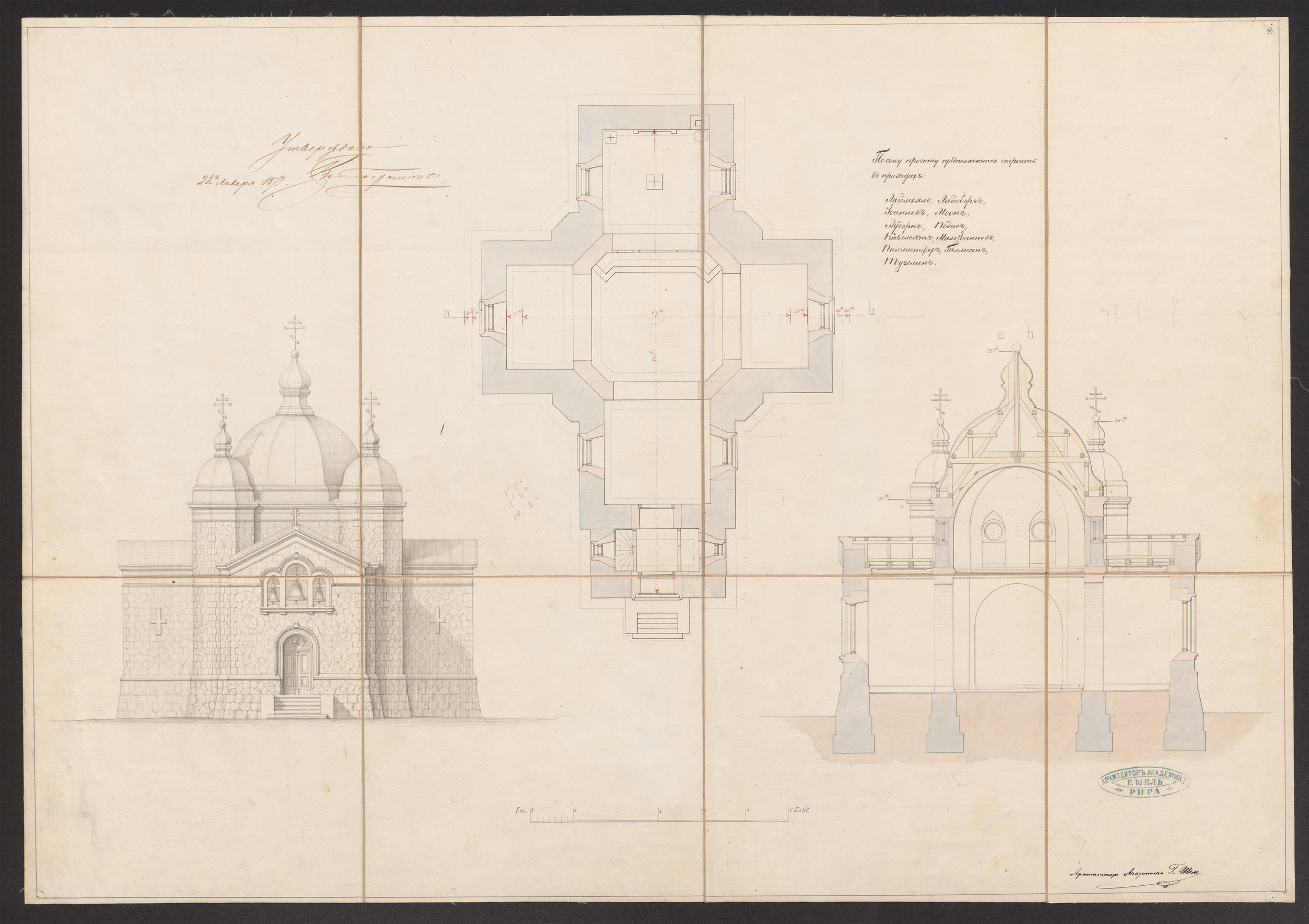

Of great interest in this period are the churches in the “Russian-Roman” style, built from cobblestone and red brick and designed by Alexander Johann Friedrich (Jānis/Ivan) Baumanis, the first Latvian architect with an academic education. Born on 29 April 1835 into the family of a Latvian ship pilot near Limbazi, he studied at the Berliner Bauakademie (1860-1862) and the St Petersburg Academy of Arts (1862-1863), where he qualified as an architect. One of the founders of the Riga Association of Architects and the leader of the Riga Latvian Society, he designed around 150 homes and public buildings, including 90 apartment blocks.

Baumanis’ Russian-Roman churches include the following. In Karula-Vissi, a stone church for 600 people, a school for 40 pupils, a parochial house, and a wooden bathhouse were built: the church was blessed 11 June 1878 by the priest Vasilii Karzov. The Khristorozhdestvenskaia church for 200 people in Võnnu was blessed on 16 September 1879 (now a Methodist church). In Valmiera, a church in the name of St Sergii Radonezh was built for 300 people: it was blessed on 16 May 1879. The Ioanno-Predtechenskaia church in Maardu was blessed on 2 September 1879 (and torn down in 1962). In Mustvee, Baumanis built a school for 100 people and a stone church with “entirely wonderful architecture” in the edinoverie parish, which was blessed on 28 May 1879 [4]. The church of St Vasilii Velikii in Vanamõisa was blessed on 7 October 1879.

With a salary of 1,800 roubles, Baumanis’ contract was extended to 1879, since he was still occupied with repairing churches in Haapsalu and Põltsamaa and building the church in Bauska, which was designed in 1878.

Bauska Orthodox church

Construction on the Georgievskaia church in Bauska began at the end of June 1879. The foundation stone was laid on 6 August 1879: it was accepted into the ecclesiastical domain on 28 November 1879 and blessed on 18 January 1881. This three-part church has the shape of an equilateral cross, although the west-east axis are slightly elongated. The main body is cube-like and crowned with five domes: the lateral projections are topped with triangular pediments. The drums take the form of richly profiled elongated octals. The lateral drums are scaled and crowned with onion domes, thereby "russifying" the church’s appearance. The central drum has a helmet-shaped dome. The main quadrangle is connected by the refectory to the narthex, above which rises a pillar-shaped bell tower, square in plan, topped with a low tent and dome. On the window openings (semicircular, decorated with frame platbands) are decorative hatches: the cornices are decorated with belts of denticles. The red brick is combined with bleached details.

Vsesviatskaia church in Riga

On the initiative of Bishop Filaret, Baumanis began designing and building one of the best Russo-Roman style churches in the Russian Empire: the Vsesviatskaia church in Riga’s old Orthodox graveyard (1881-1884). It has a three-part plan and a semicircular apse. The egg-shaped roof and crowning bulbous dome are decorated with four semicircular bodies attached to the edges and Venetian window openings. To the west is a pillar-shaped bell tower with a refectory (1868–1870), crowned with a low tent and dome (like the church in Bausk). Brick décor is used for the buttresses, the framing of the semicircular windows, the belts of the arches, and the windows on the façades. The refectory has a flat ceiling: in the centre, an octagonal light drum rests on massive corner supports. The roof of the transept is covered with semicircular vaults. The Berlin churches of St Mark (Markuskirche, 1848–1850, architects G.L. Runge and A. Stüler: now destroyed) and St Thomas (Thomaskirche, 1865-1869, architect F. Adler: based on the church of San Vitale in Ravenna) were the prototypes for the “italianizing” decoration, although this does not deprive Baumanis’ building of its originality. The bell towers of these churches in Riga and Bausk are reminiscent of the monastery bell towers designed by M. A. Shchrupov for the Rekonskaia hermitage and by M. D. Bykovskii for the Moscow Strastnii monastery.

Bamanis was the last specialist in Orthodox church construction to receive a regular salary during the church building campaign.

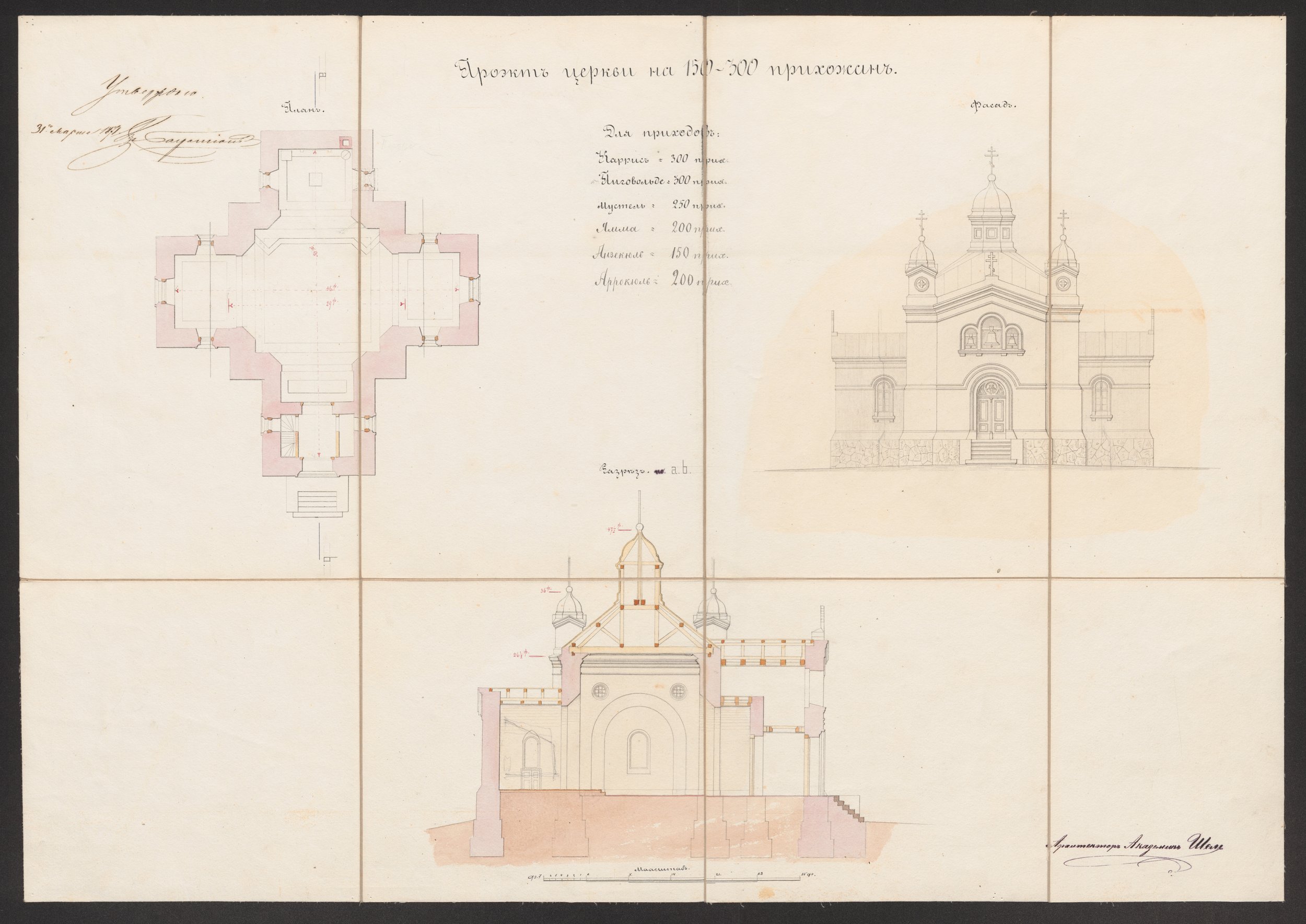

Planned by R. A. Pflug [5] in 1875, a few other churches made of cobblestone and red brick were finished under Bishop Filaret. There was the Petropavlovskaia church in Koknese, blessed in 1878 (destroyed in 1965); the Georgievskaia church in Jõõpre, blessed on 2 September 1879; the Krestozdvizhenskaia church in Vestiena for 450-500 people and blessed on 27 May 1880; and the Ioanno-Predtechenskaia church in Lēdurga for 200-300 people and blessed on 25 October 1881.

Pflug ceased working on village churches when he started to work on the decoration of the Khristorozhdestvenski cathedral in Riga, receiving a position connected with this from the Ministry of Internal Affairs on 21 June 1878. Under Filaret, the basic construction work on the cathedral was completed and the decorative work accomplished [6]. Originally, it was proposed to order icons from the local craftsman P A. Zyrkov, who had worked on churches in Riga and Valga. In the end, however, the artistic work was completed by famous masters predominately from the academic world: with flourishes of the Byzantine style, the murals were done by F. S. Zhuravlev and A. I. Korzukhin, while the icons were painted by V. V. Vasilev, K. B. Venig (a native of Tallinn), V. P. Vereshchagin (1835-1909), and P. M. Shamshin. Filaret himself composed the programme for the murals and the placement of icons on the iconostases. On 1 October 1881, in a letter to Pflug, Filaret expressed the desire that the art should “have an artistic Byzantine character for harmony with the church’s architecture.” The goldwork was provided by the craftsmen Borel from Vilnius and E. Ivanov from St Petersburg. The cupolas were painted light blue. The heating system, using pottery kilns and ventilation, was developed by the engineer I. Flovitskii (there were also four Russian stoves in the basement and a cast iron fireplace): the water supply was designed by I. A. Bok. A considerable number of the craftsmen employed were from Riga. Pflug also designed the cathedral’s bell tower: with an estimated cost of 60,163 roubles, the cathedral’s blueprints were approved by the emperor on 16 May 1880. The reason for this high cost and the need for imperial approval was that Emperor Alexander II donated 12 bells to the cathedral: due to their size, they could not be placed as originally intended. Under Filaret, Pflug finished another Riga church in the Byzantine style –the cross-shaped Pokrovskaia cemetery church and its bell tower (1876-1877).

Interior of the Riga Khristorozhdestvenskii cathedral

In March 1880, Filaret had a conversation with his good acquaintance, the outstanding missionary St Nikolai (Kasatkin) [7] on the subject of how the episcopal manor (“a vicar’s holiday home”, “the best on the outskirts of Dorpat”) would give its income from rent and other payments to support the mission in Japan. St Nikolai was in 1880 consecrated as the bishop of Reval, a suffgrancy of Riga diocese.

In 1880, Filaret also rebuilt and founded the Illukst Rozhdestvo-Bogoroditskii convent and its school [8]. However, Filaret’s activities, in particular his conflict with the Latvian Archpriest Mikhail Dreksler [9], first rector of the seminary (1872-1880), caused displeasure in the Holy Synod. “One can be sent to Riga as a bishop only as a punishment. Let them send me to Siberia or retire me to a remote monastery – only take me away from here!” said Bishop Filaret in pique [10]. K. P. Pobedonostsev, chief procurator of the Synod, openly wrote to Metropolitan Isidor (Nikol’skii) of St Petersburg on 11 February 1882 about removing him from the cathedra in order “to prevent complete disorder in the diocese” [11]. The turmoil could not fail to have an effect on the hierarch’s health: he suddenly died of a heart attack on 23 February 1882, in the fifty-eighth year of his life. He was buried in the crypt under the right kliros of the Riga Petropavlvoskii cathedral [12]. After the closure of the church in October 1963, the bishop’s remains were reburied by the south wall of the Preobrazhenskii church of the Riga convent’s hermitage near Jelgava [13]: the grave is marked by a black granite cross.

Riga Khristorozhdestvenskii cathedral

During Filaret’s brief tenure in Riga diocese, the construction of new churches was above all driven by the need for churches among the Latvian and Estonian peasants who had converted to Orthodoxy in the 1840s: it wholly depend on state financing, which was constantly reduced. Nonetheless, churches continued to be built as complexes, together with schools and parochial homes, as was common in the Baltic region. The number of churches under this bishop rose to 182. Their architecture shows an eclectic heterogeneity of styles, characteristic of the reign of Alexander II even in the conservative arena of church architecture: the “Russian-Roman” (Russian and Byzantine) style predominated. After the accession of Alexander III, the Russian style became the most widespread. In Riga diocese, this happened after the death of Bishop Filaret, which concluded the church construction campaign of 1870-1878, the most important era of Orthodox temple building in the Baltic.

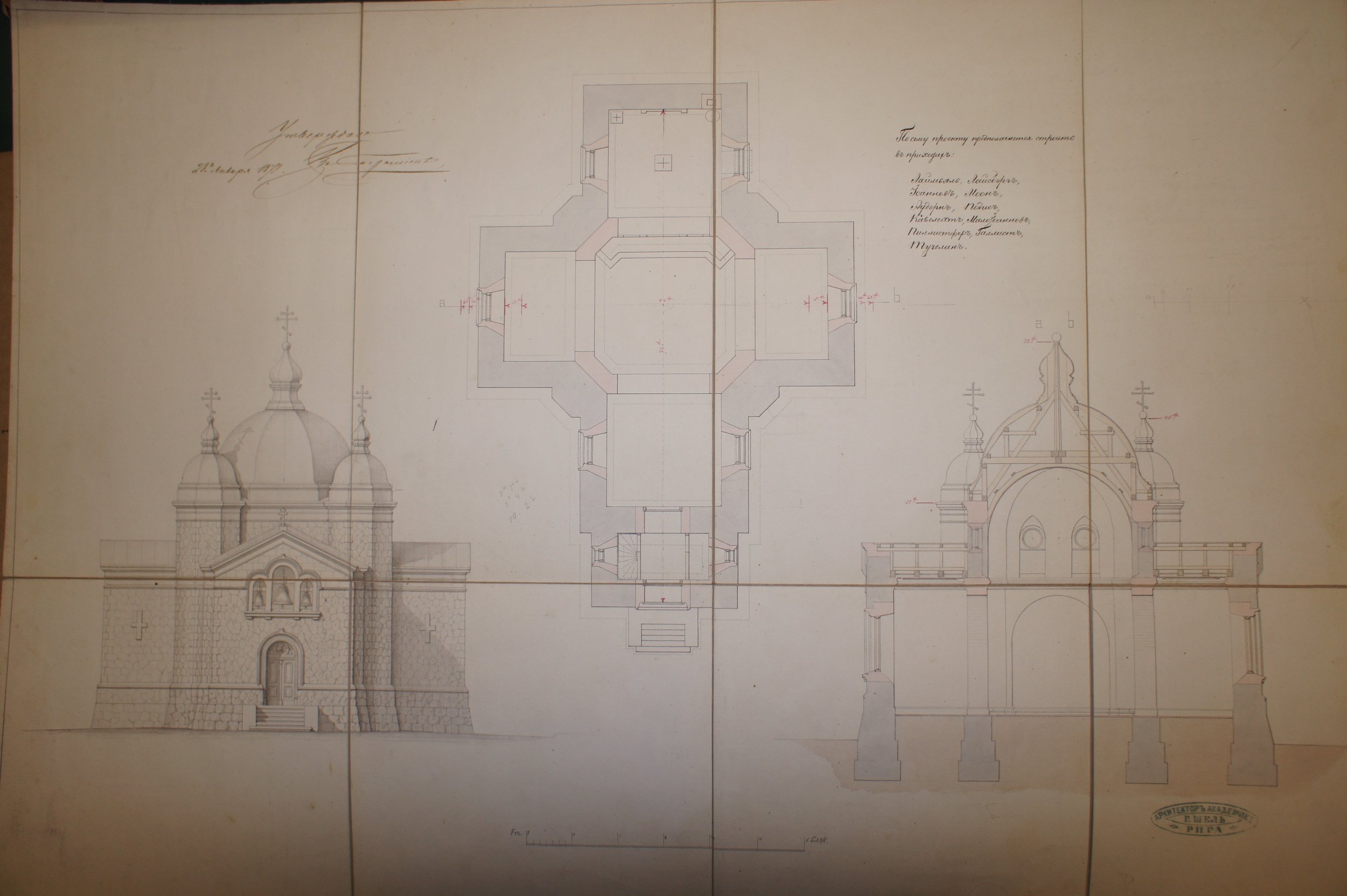

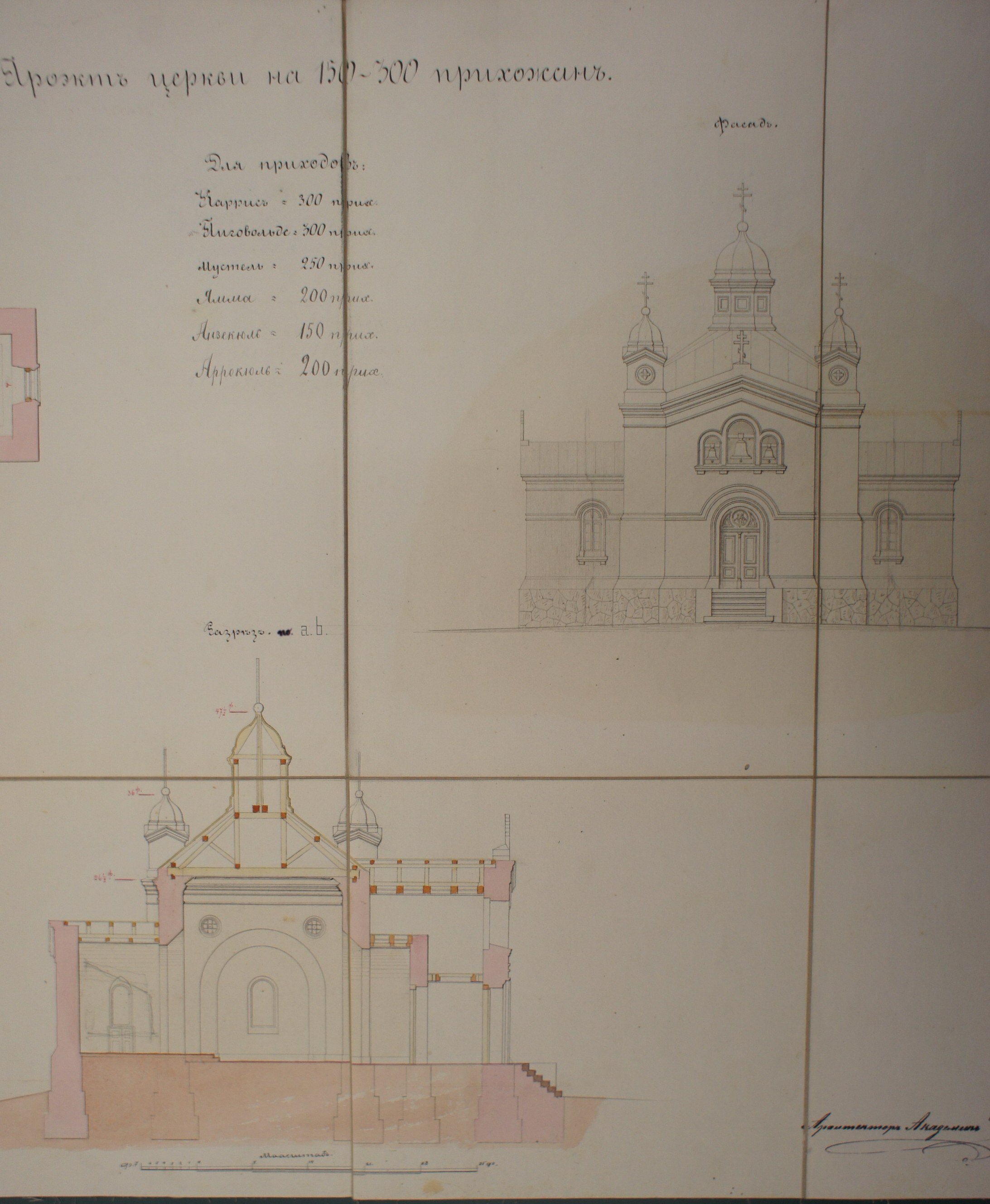

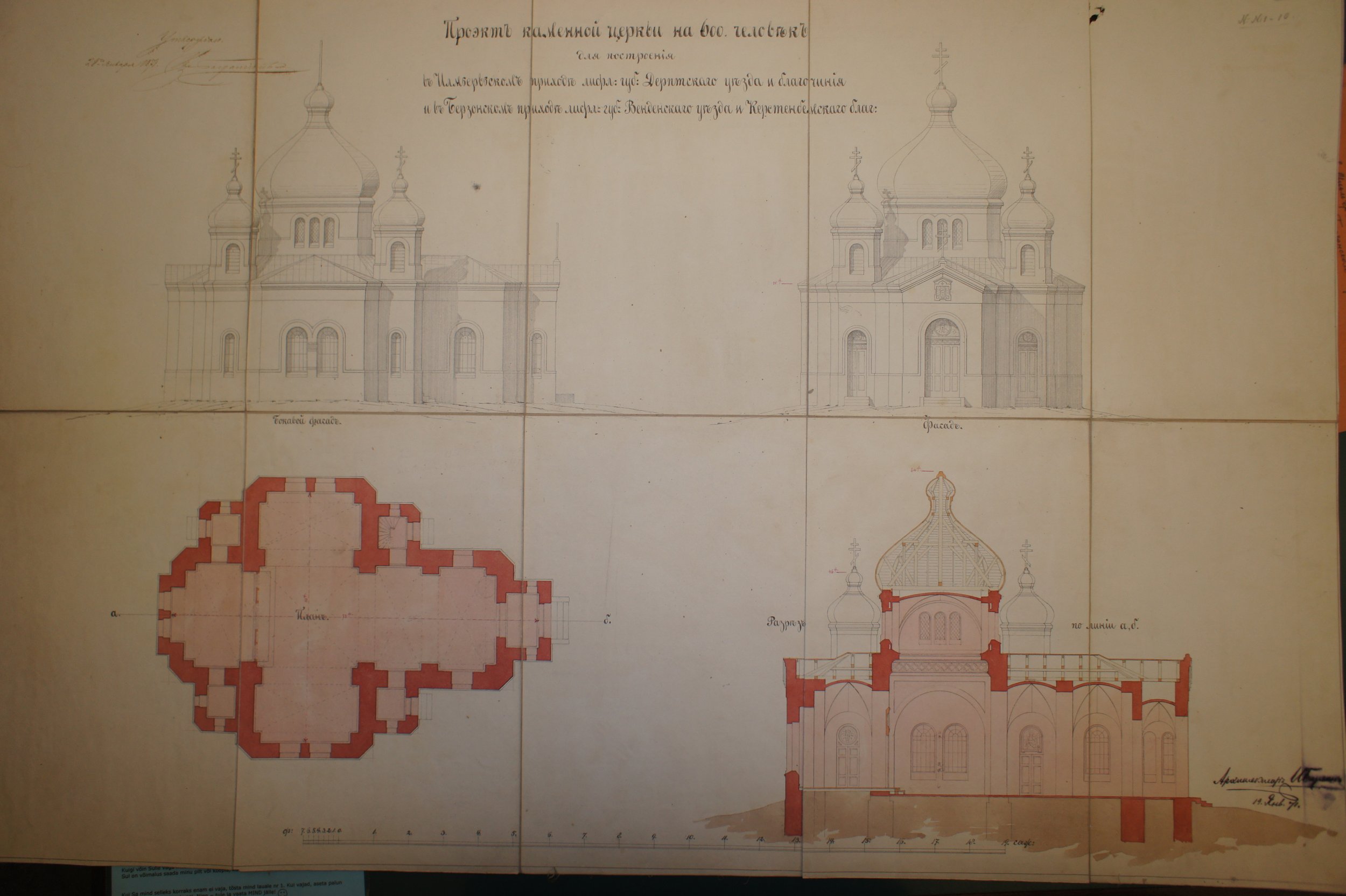

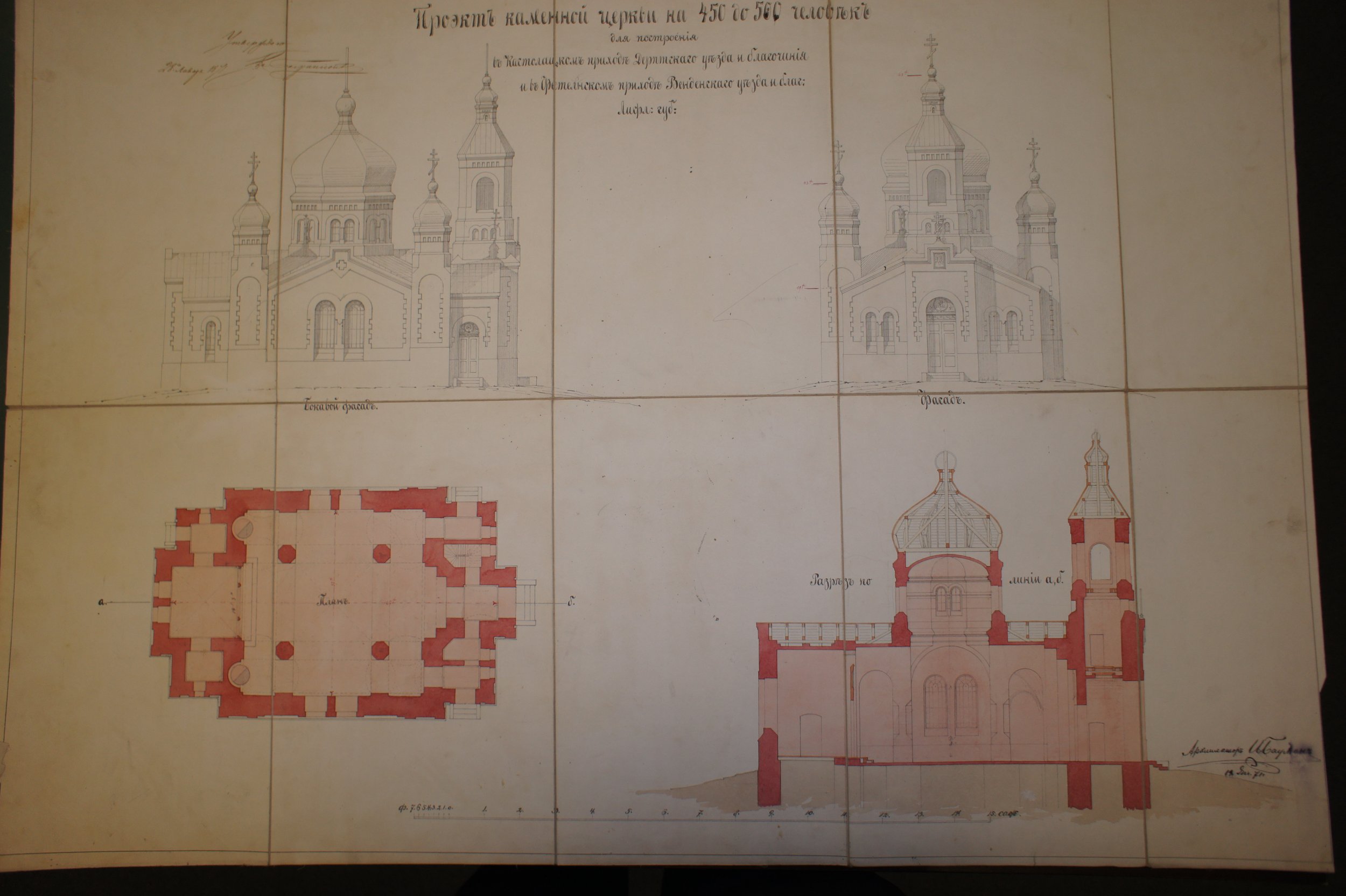

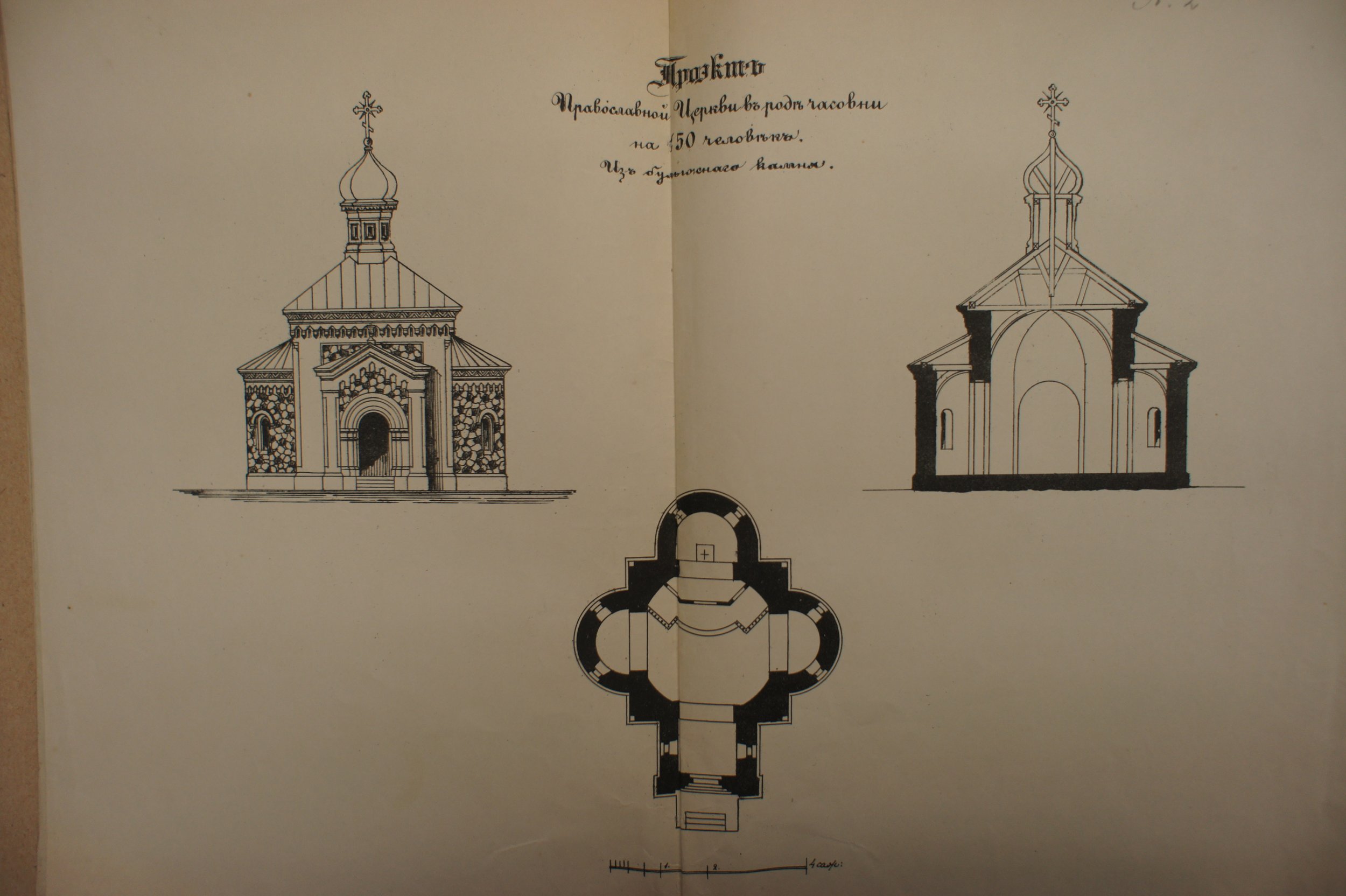

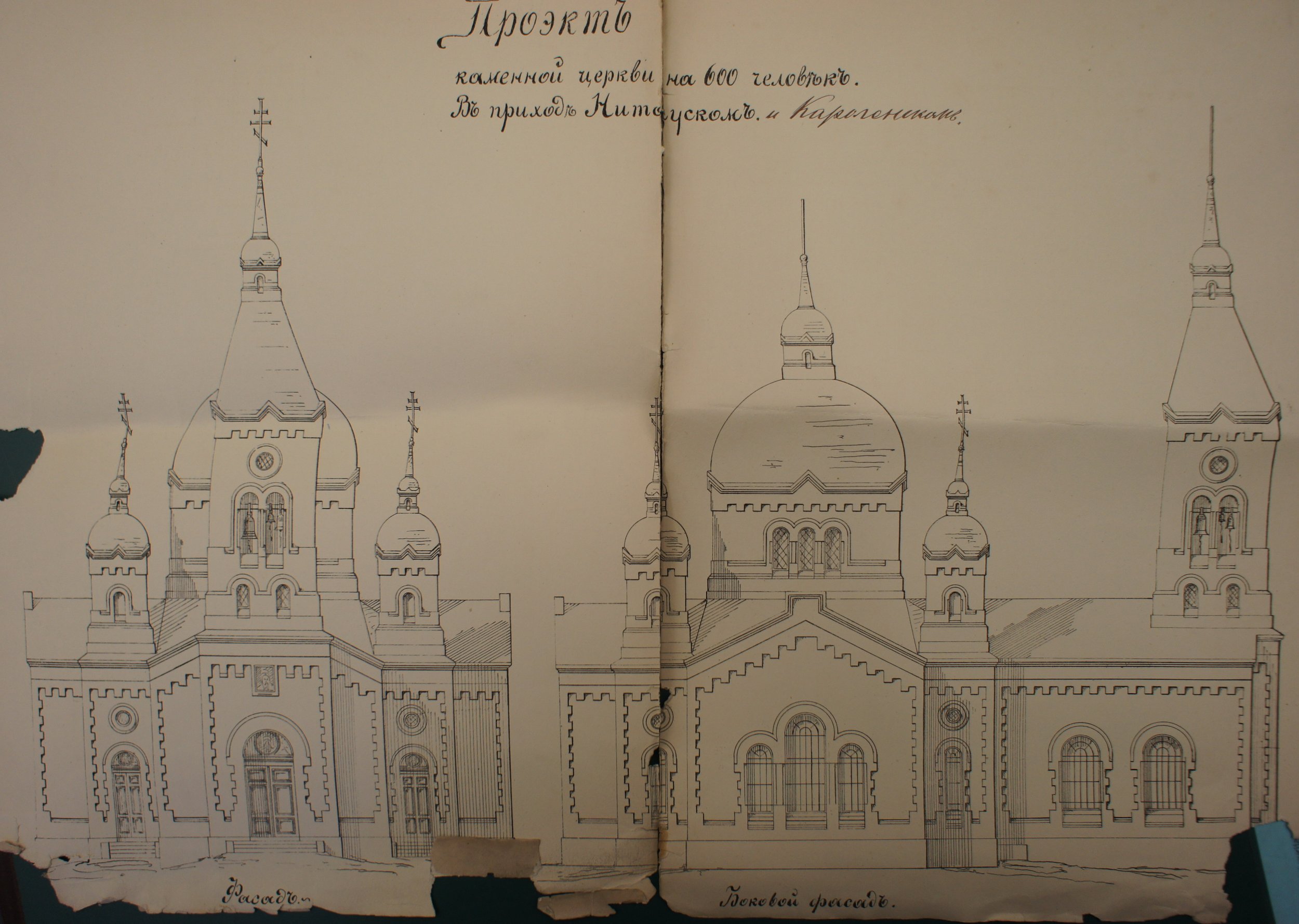

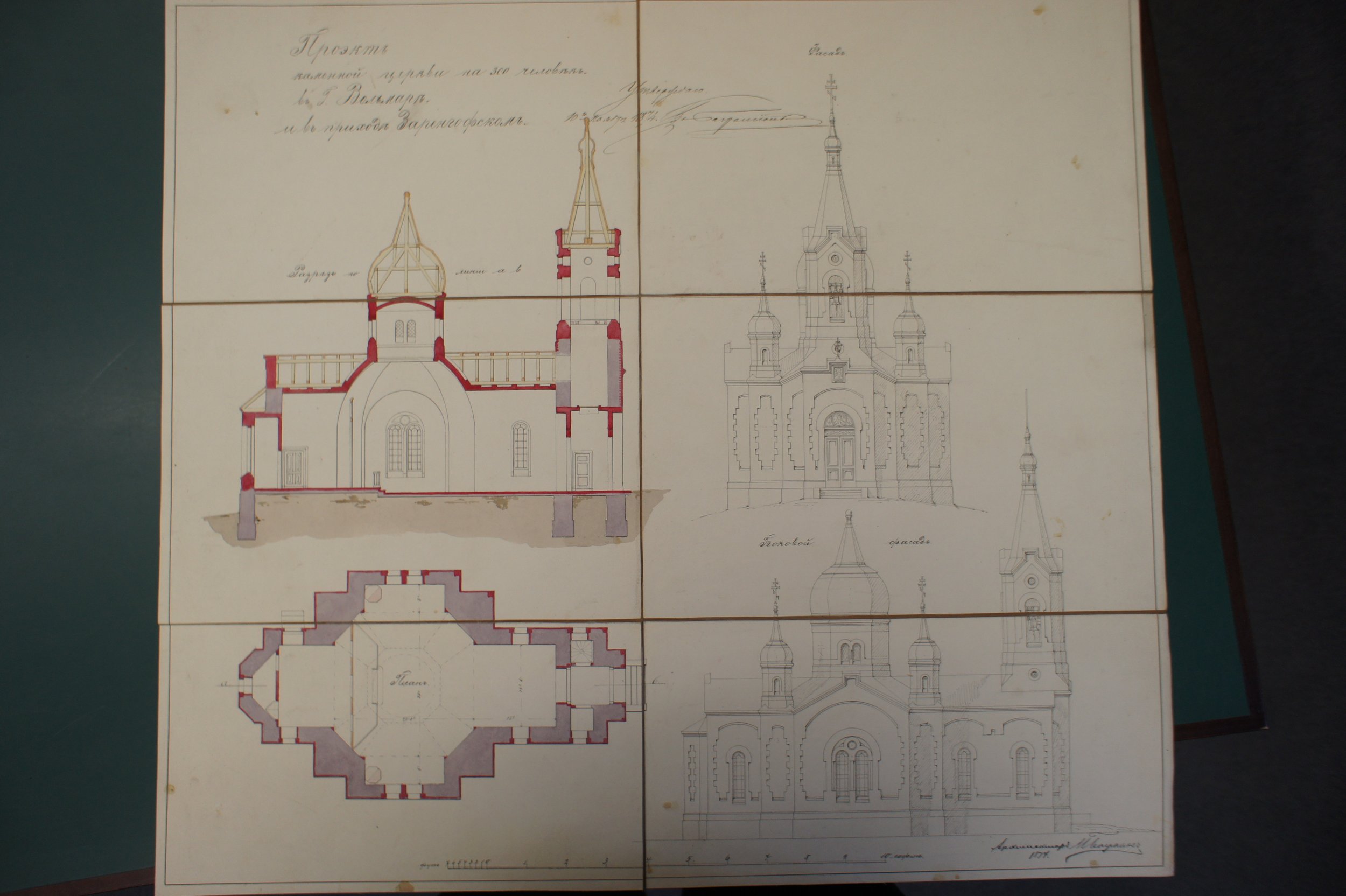

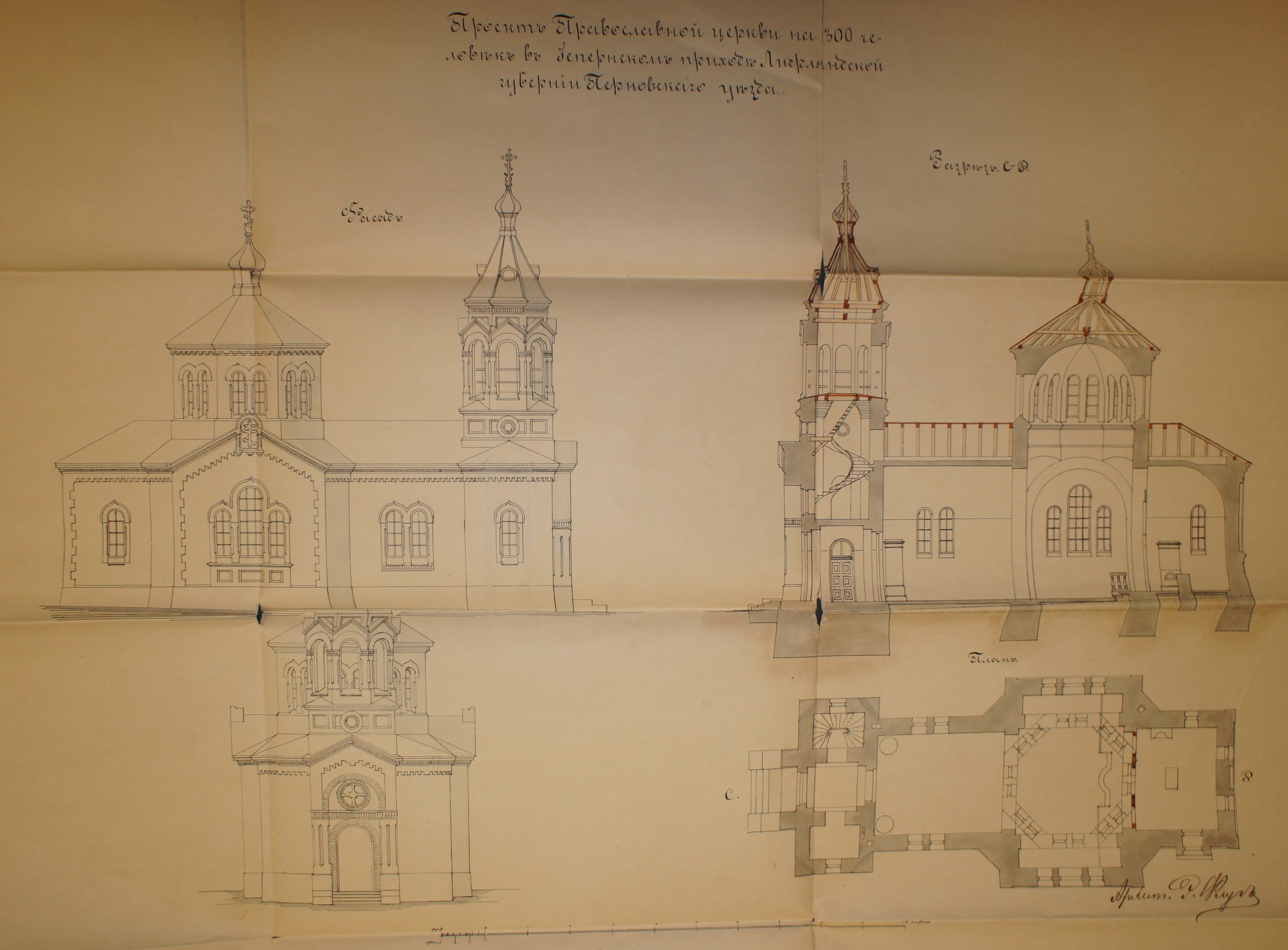

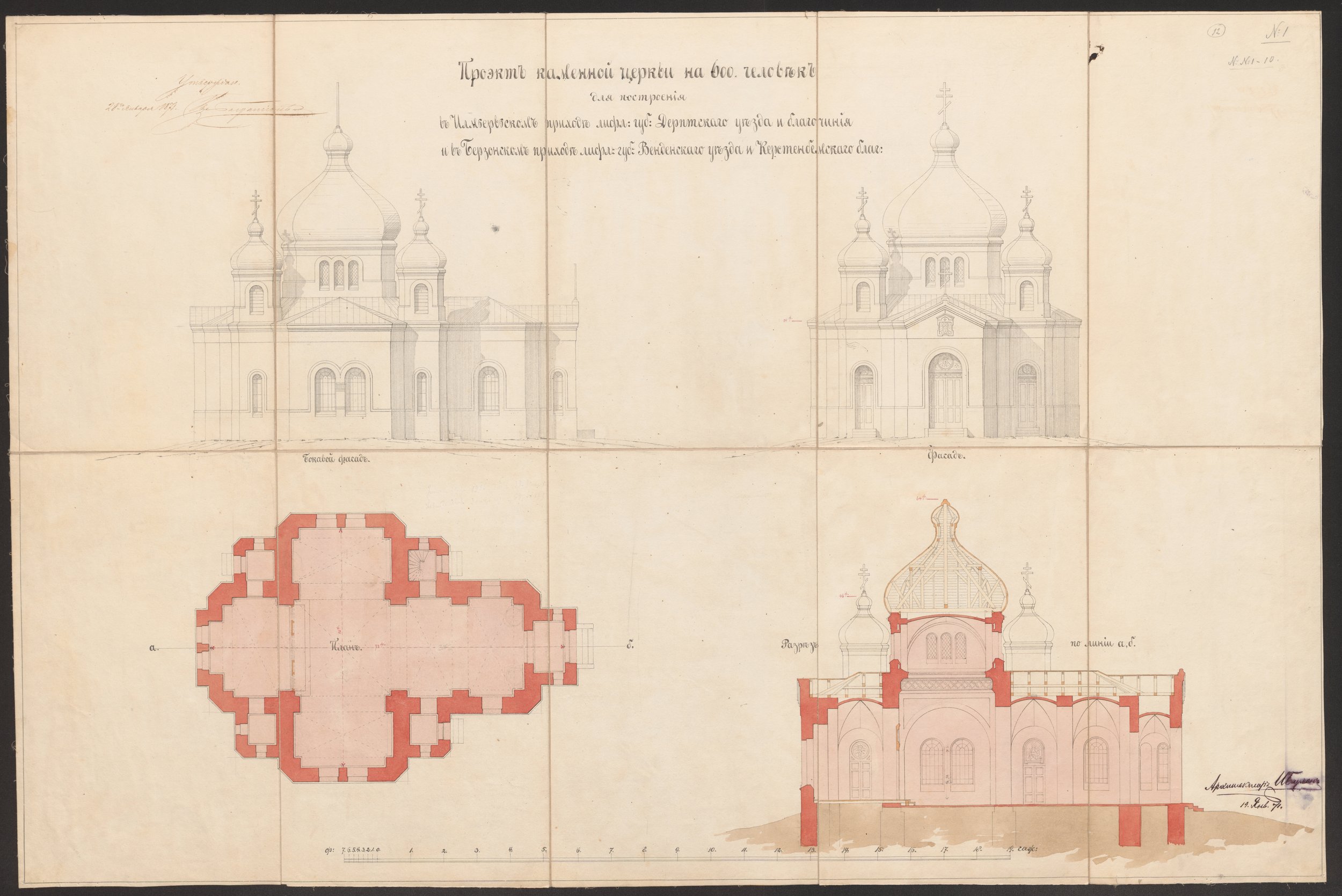

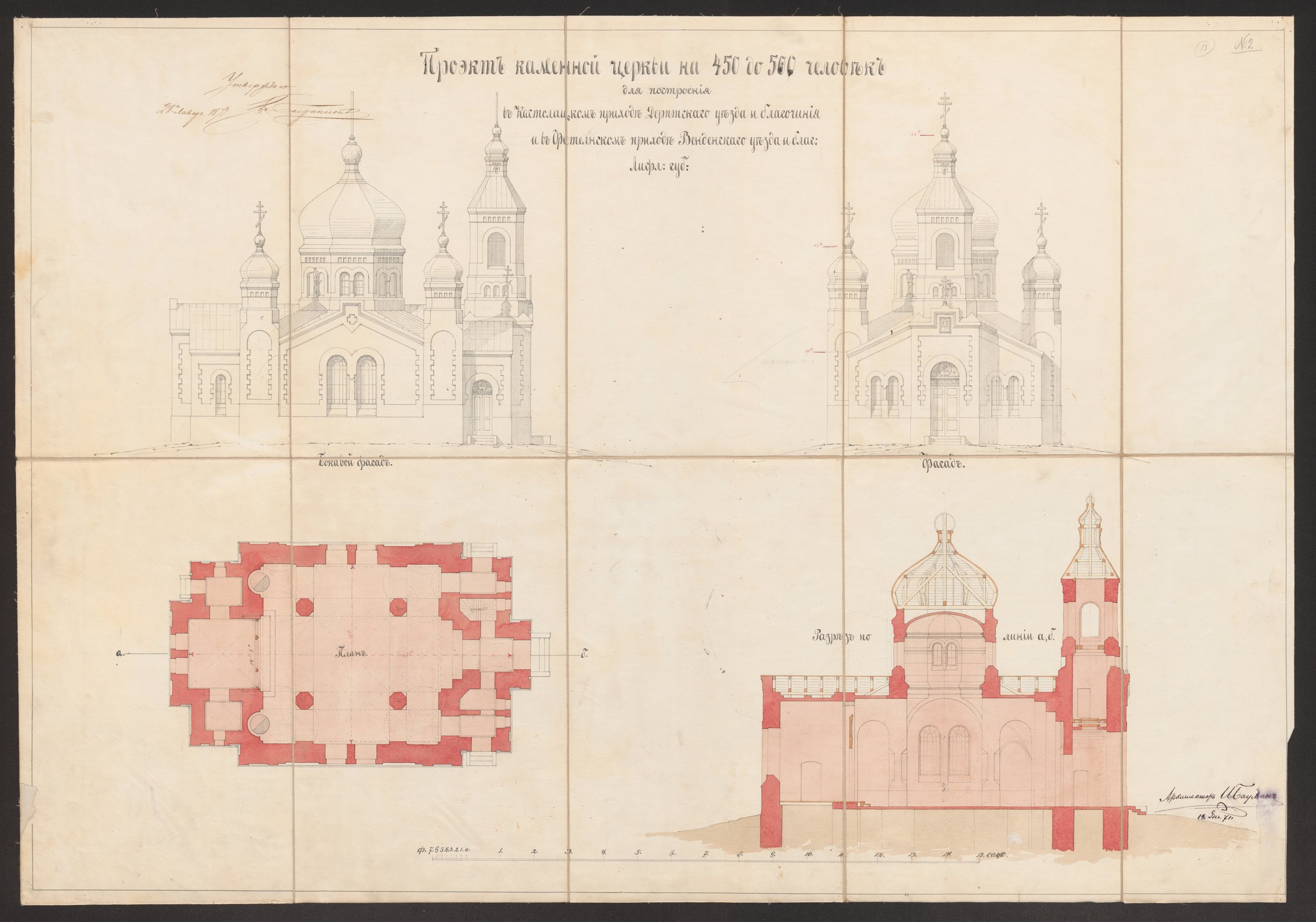

Gallery of contemporary architectural plans

Notes

[1] Filaret was bishop of Uman (a suffrancy of the Kiev metropolitan) from 1874 to 1877 and rector of the Kiev Ecclesiastical Academy (one of the Orthodox Church’s four university-level institutions) from 1860 to 1877. As then, Filaret is most famous today for the reforms he introduced into the academy.

[2] The campaign for church construction in the Baltic lasted throughout the 1870s: it was in part designed to provide proper church facilities for converts from the 1840s, who often had to endure cheapily constructed and inhospitable temples.

[3] The Riga Polytechnical Institute was founded in 1862.

[4] Obozrenie tserkvei, shkol i prikhodov preosviashhennym Arseniem, episkopom Rizhskim i Mitavskim v 1891 g. (Riga, 1892), p. 93. Edinoverie was a movement in Russian Orthodoxy which allowed Old Believer converts to use their own particular rituals and church books.

[5] Robert Pflug (1832-1885): along with Baumanis, he designed the House of the Livland Noble Corporation, which is today the building of the Latvian parliament.

[6] Work was completed on the cathedral in 1883.

[7] St Nikolai Kasatkin (1836-1912) is mainly known as the apostle to Japan, founding and participating in the Orthodox mission there from 1861 until his death. He became archbishop of all Japan in 1907.

[8] The Illukst convent was founded in 1881.

[9] Educated at the Moscow Ecclesiastical Academy, Archpriest Mikhail Mikhailovich Dreksler (1840-1885) was rector of the seminary from 1870 to 1880.

[10] Manuil (Lemeshevskij), mitr. Russkie pravoslavnye ierakrhi. 992–1892. Vol. 3. (Moscow, 2004).

[11] LVVA, f. 1462, apr. 1, l. 181, lp. 144.

[12] The Riga Petropavlovskii cathedral was built as wooden church in the time of Peter the Great. It became a cathedral when Riga was made an independent diocese in 1850. Following closure by the Soviet authorities, it today houses the Ave Sol concert hall. Liturgies are still held there.

[13] The Spaso-Preobrazhenskaia hermitage was founded near Jelgava in 1894-96 as part of the Riga Troitsko-Sergieev convent.

AUTHOR

Archpriest Aleksandr Bertash

Source

Original article (translation edited): “Arkhitektura i stroitel’stvo khramov Rizhskoi eparkhii pri episkope Filarete (Filaretove)”, Pravoslavie v Baltii, no. 9 (2020), 37-46.

Translator

James M. White